On Supercharging Your Chapters

By Christine Carron

Many years ago, I attended a session on revision during Grubstreet’s annual Muse and the Marketplace conference led by Ann Hood. A tip I learned in that session remains one of the most practical writing tips I’ve ever received. It was all about what causes flat chapters (and scenes) and how to avoid them.

She referred to this technique as her Plus/Minus System, and she credited the framework to a principle she learned in Robert McKee’s screenwriting class.* Here is the tip: A chapter reads as flat if it starts and ends on the same emotional charge. Positive to positive equals flat experience for the reader. Negative to negative results in the same experience of flatness.

Flat Chapter Structures

The solution? Make sure the beginnings and endings of your chapters (and scenes) have polarized emotional charges.**

Supercharged Chapter Structures

When I found flat chapters in my own work applying this filter, the problem was often caused by where I ended a chapter. Before this technique, I thought a chapter was flat because not enough happened; it was boring. But now I could see even in chapters where a lot was happening, there would be a clear moment toward the end where the charge was vibrating in opposition to the beginning, but then I had written beyond that moment, flattening the emotional oomph.

So, a key point to remember is that a flat chapter is not related to how much action is or is not happening within the chapter; it has to do with the energy/emotional interplay between the ending and the beginning.

Another important caveat is that positive and negative are all relative. Take for example, the first chapter in Pet by Akwaeke Emezi. The chapter’s opening line: There shouldn't be any monsters left in Lucille.

I don’t know about you, but I’m feeling like the Jaws theme music has thumped onto the stage. Dah-DUHM. We are starting with a little dread, right? Shouldn't be any monsters hints strongly there still might be monsters. At first glance, it seems like we may be starting with negative charge.

What follows is a masterful chapter that introduces an evocative, allegorical story world; the main character Jam who was born after the time of the monsters; Jam’s quest to learn about the non-human angels who combated the monsters; her transition surgery; her friends and family—i.e., a rich, full chapter.

But then, even though the chapter started on that dread note, Emezi ends the chapter not on an uplift but instead amps up the dread, meaning negative to negative/negative, which is another version of positive to negative. Here is the ending:

. . . the problem is, when you think you've been without monsters for so long, sometimes you forget what they look like, what they sound like, no matter how much remembering your education urges you to do. It's not the same when the monsters are gone. You're only remembering shadows of them, stories that seemed to be limited to the pages or screens you read them from. Flat and dull things. So, yes, people forget. But forgetting is dangerous.

Forgetting is how the monsters come back.

Emezi goes from hinting of monsters to a shivery certainty that they are coming, through the forgetting. Which exemplifies what Robert McKee meant when he wrote: “. . . a story can go from positive to positive or negative to negative, if the contrast between these events is so great, in retrospect the first takes on shades of its opposite.”

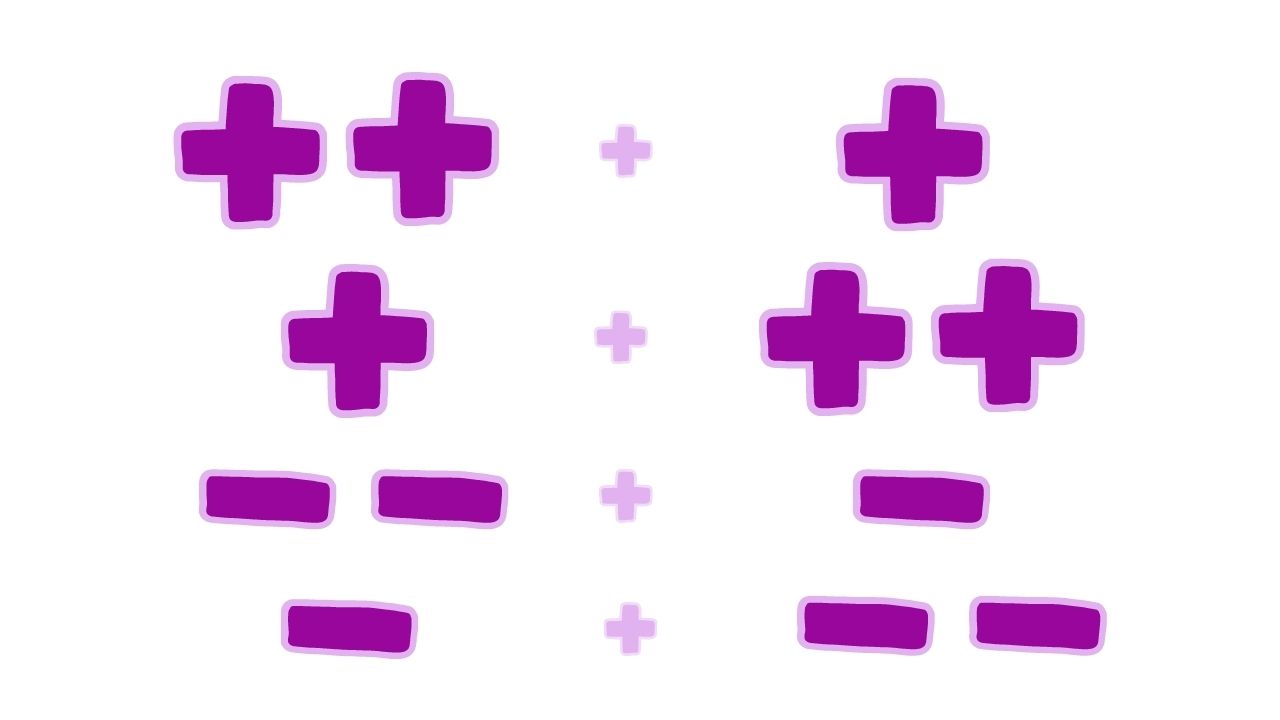

Supercharged Chapter Structure Variations

- See the technique in the wild. Take a couple of your favorite books and analyze some of the chapters to determine the emotional charge of their beginnings and endings.

- Apply the technique while drafting. When you are designing your next chapter or scene, consciously attend to the emotional polarization of the beginning and end.

- Use the technique as a revision tool. Make a spreadsheet and list the emotion and charge of the beginning and endings of every chapter. Revisit any chapters that are not polarized to amp up the charge differential.

Don't miss a single dollop of Goodjelly

Subscribe for the Latest Blog Posts & Exclusive Offers!

You can easily unsubscribe at any time.